Impact of the reformed Working Hours Act and the COVID-19 pandemic on working time in the social welfare and health care sector

The COVID-19 forced over one million Finns to work remotely. Most of the work tasks in the social welfare and health care sector were still bound to the same location as before. Nonetheless, the COVID-19 pandemic introduced enormous changes in the social welfare and health care sector. In addition, the reformed Working Hours Act entered into force already slightly before the COVID-19 pandemic broke out.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the reformed Working Hours Act

The social welfare and health care sector represented the most critical frontier of in-person work during the COVID-19 pandemic, bearing responsibility for treatment of COVID-19 patients. Additionally, many of the employees in the sector have been under constant risk of exposure due to their work. Priorities during the COVID-19 pandemic, with changing guidelines transformed work in the social welfare and health care sector at a rapid pace. The pandemic introduced heavy protective equipment and increased workload especially at intensive care units. Simultaneously, other health care operations were shrunk, which led to an increase in the backlog of care.

The new Working Hours Act entered into force in early 2020. The law requires at least 11 hours of rest time between work shifts. On the other hand, the Emergency Powers Act related to the COVID-19 pandemic enabled deviating from regulations regarding overtime and rest times, when in effect.

Factors related to working time and workload changed rapidly in the social welfare and health care sector in early 2020. But how did working time change in hospital districts and in cities social welfare and health care units?

Working time characteristics in shift work units

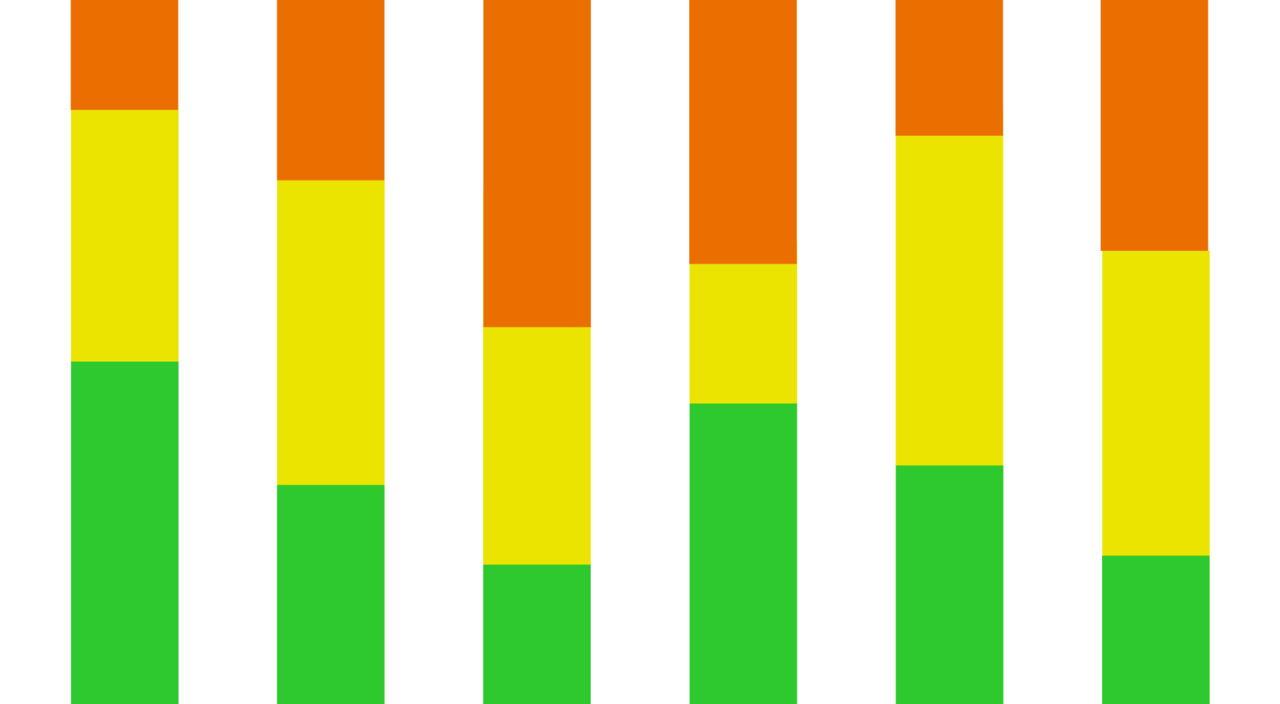

Working time characteristics refer to characteristics of working time that can also constitute stress factors related to working hours. We look at working time characteristics and their change during the years 2019–2021, a period ranging from before and after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and the introduction of the new Working Hours Act. We divided the working time characteristics into characteristics related to length of working time and recovery and ones related to the opportunities to influence working time (see also the Traffic light model for assessing working time). We also analysed the development of sickness absences.

We examine work units in the social welfare and health care sector that do shift work and that monitor realised working time characteristics for each three-week planning period during the years 2019–2021.

A total of 758 work units were chosen for this examination, of which 503 are from three hospital districts and 255 from social services of five cities. When the exceptional conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic started in the spring 2020, a total of over 20,000 employees worked in these work units.

Length of working time

The average length of work shift remained unchanged in 2019–2021. The graph demonstrates a very small increase in the length of work shift, especially during the summer holiday season. Onset of the exceptional circumstances related to the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 did not cause deviations in the average length of work shifts. Work shifts in hospital district are 15 minutes longer than in cities’ social welfare service, on average

There have been almost no changes in the average number of weekly hours or consecutive working days with the COVID-19 pandemic. There are very significant seasonal changes in the number of consecutive working days, which aligns with the holiday seasons.

(Text continues after graph)

Figure 1. Working time characteristics related to length of working time from the beginning of 2019 until the end of 2021.

Recovery

The share of short shift intervals of less than 11 hours of all shift intervals decreased to less than half as a result of the changes to the Working Hours Act in 2020. The use of short shift intervals started to slowly grow again later, but the changes would not seem to be related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Changes to the Working Hours Act, which limited the number of short shift intervals, reduced them rapidly.

There are seasonal changes in the average shift interval lengths, which has remained the same during the examined period, even after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 2. Working time characteristics related to recovery from the beginning of 2019 until the end of 2021

Opportunities to influence working time

The share of fulfilled shift requests was fairly high in 2019–2021. The shift requests of city employees were fulfilled slightly more often than those of hospital district employees. After the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a short dip in the percentage of fulfilled shift requests of hospital district employees, but the situation returned to normal rapidly.

Shift requests would seem to be fulfilled evenly throughout the year, also during holiday seasons.

Figure 3. Working time characteristics related to fulfilled shift requests from the beginning of 2019 until the end of 2021

Sickness absences

Stress caused by working time, together with the COVID-19 pandemic, had an impact on sickness absence in the social welfare and health care sector. The average number of sickness absence days per period is slightly higher in hospital districts than for employees of cities’ social welfare services. During the three year review period, the number of sickness absence reached its peak immediately after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in early March 2020. At that time, employees of both hospital districts and cities had an average of 1.7 sickness absence days during a three-week work shift planning period. The number of sickness absences increased immediately after the start of the COVID-19 and as quarantine orders entered into force. However, the number decreased soon after the quarantine orders had been in force for a short time.

There is significant seasonal changes in sickness absences and they are most prevalent during the seasonal influenza.

Figure 4. Working time characteristics related to sickness absences from the beginning of 2019 until the end of 2021

The working time characteristics changed quite little at average, but there may still have been high-stress peaks

As summary, it can be said that no dramatic changes in the working time characteristics related to the COVID-19 pandemic can be observed in the social welfare and health care sector. On the other hand, the reformed Working Hours Act decreased the number of short shift intervals rapidly in early 2020. Short shift intervals hamper recovery between work shifts and increase the number of sickness absences and the risk of occupational accidents. The COVID-19 pandemic, which started a few months later, had no impact on the number of short shift intervals. Opportunities to influence working time decreased momentarily at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic especially in hospital districts, but returned to normal quickly.

It is likely that directing resources to activities related to treating the COVID-19 pandemic have managed to decrease stress related to working times. Stress related to working time has been successfully managed by assigning employees to new work tasks, recruiting more workforce and limiting holidays and days off on a case-by-case basis.

In the light of working time characteristics, work in hospitals were organized after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic just as before. However, working time is only one factor that has an effect on the stressfulness of work. Hidden under the averages of the entire social welfare and health care sector personnel, there may be even very significant high-stress peaks, especially in the case of employees who treated COVID-19 patients.

Read more

Creative Commons License

The publication is licensed under Creative Commons 4.0 International -license.